EXPERIENCES

Take to the open seas, let yourself be carried away by the trade winds, explore elsewhere in complete autonomy... Each navigation aboard an Allures sailboat is a singular experience, a subtle balance between mastery, emotion and contemplation. Here, our owners share their adventures with you. Whether they've rounded a mythical cape, dropped anchor in a forgotten bay or simply savored the silence of a night at anchor, they share their choices, their challenges, their joys - and that unique feeling of being truly free.

On the Viking Route: from Europe to Greenland aboard the Allures 51.9

Growlers, Greenland and the New World: CASTELLA sails the Viking Route

Following our Swiss owners Marianne and Markus on their Allures 51.9

The scientific community has widely accepted that it wasn’t Christopher Columbus who discovered the American continent, but a group of Icelandic Vikings about half a century earlier. A man named Leif Eriksson arrived around the year 1000 in the “New World”, following his father’s footsteps who had already begun settling in Greenland. Even though the Vikings’ American settlements didn’t last longer than a few years, the notion of the fearless Norsemen crossing the stormy, ice-laden Northern Ocean in their square-rigged longships still fascinates us. The “Viking Route” has become a must-do for adventurous sailors who are drawn to the Arctic. Such as Marianne and Markus.

The “Viking Route” has become a must-do for adventurous sailors who are drawn to the Arctic. Such as Marianne and Markus.

The right boat for a trip to Greenland: Meet CASTELLA, an Allures 51.9

Back in 2019, the experienced sailing couple signed the contract for the first of the new Allures 51.9 yachts.

“An aluminum hull, variable draft and of course insulation and heating were basic necessities to sail that far north,” Markus insists. “Our decision for Allures was also driven by their spotless track record in making the benchmark for exploration yachts worldwide.”

Markus should know: he is a graduate marine scientist, sailing for over 40 years on yachts as well as on tall ships. Marianne, his wife, spent her life on and under water, being a keen diver. She started sailing on a J/88 back in Switzerland and has been intensively offshore sailing for more than 10 years. “My home is my CASTELLA,” says Markus and smiles. For him, the ruggedness, stiffness and consistent focus of Allures on real blue water sailing make her perfect for the couple. “She is big enough for hosting guests and friends, but can easily be managed as a couple. She is reliable in very adverse conditions, be it in the far north or in the tropics. A true go-anywhere yacht.”

For CASTELLA and her crew, taking on the Viking Route was set to be the first major offshore adventure, starting right here in Cherbourg at the shipyard where the boat had been built.

“She is big enough for hosting guests and friends, but can easily be managed as a couple. She is reliable in very adverse conditions, be it in the far north or in the tropics. A true go-anywhere yacht.”

First leg to Iceland: Of calms and glowing lava streams

After her first two years in French and British waters, CASTELLA set sail from Cherbourg at the end of March 2024 for the Viking Route. There was still a good chance of encountering strong winter storms coming in from the west, but for the first leg to Ireland, conditions remained manageable. At times, the engine had to take over. Fortunately, because it failed mid-way due to a defective oil pressure sensor.

After being adrift for some hours, the boat was towed by the RNLI into the small harbour of Arklow, south of Dublin. After a quick repair, CASTELLA set sail again along the eastern Irish coast and up to the western Scottish islands such as Islay, visiting Oban and Ullapool. From Stornoway, the crew headed into the open sea, bound for the Faroe Islands.

.jpeg)

May it be the meteorological magic of the couple’s route planning or (again) due to the mercy of Poseidon, CASTELLA meet a nice calm seas and following winds — although they would have appreciated 5 or so extra knots of wind. This gentle sailing would have been much more pleasant without the frosty nights and foggy days, a sign of the harsher weather awaiting them farther north. As much as they would have loved to spend more time discovering the beauty of the Faroe Islands, they stopped only twice, because reaching Greenland was their true goal. After waiting for a suitable weather window, CASTELLA set sail for the approximately 450 nautical miles to the southern tip of Iceland.

Arriving on Vestmannaeyjar, or Westman Islands, the crew sailed on to the capital Reykjavik, passing the impressive volcanic chasm of Grindavik: The glow of molten lava was visible from the boat, which was a both fascinating and awe inspiring occasion. CASTELLA remained in the harbour of Reykjavik for a few weeks as the crew had to wait for the ice belt to shrink, which was at that time still blocking the passage to Greenland.

.jpeg)

In fact, Marianne says that sailing in the Northern hemisphere is – much more than ordinary sailors are used to it – prone to an ever changing weather. Weather windows, both in terms of winds and waves, but also in terms of the ice situation, have to be thoroughly calculated. And often waited for. That said, the second leg to Greenland had to be skipped by weeks until, at last, the ice finally loosened its strength and gave way.

In fact, Marianne says that sailing in the Northern hemisphere is – much more than ordinary sailors are used to it – prone to an ever changing weather.

Closely monitoring the weather: Icebergs ahead!

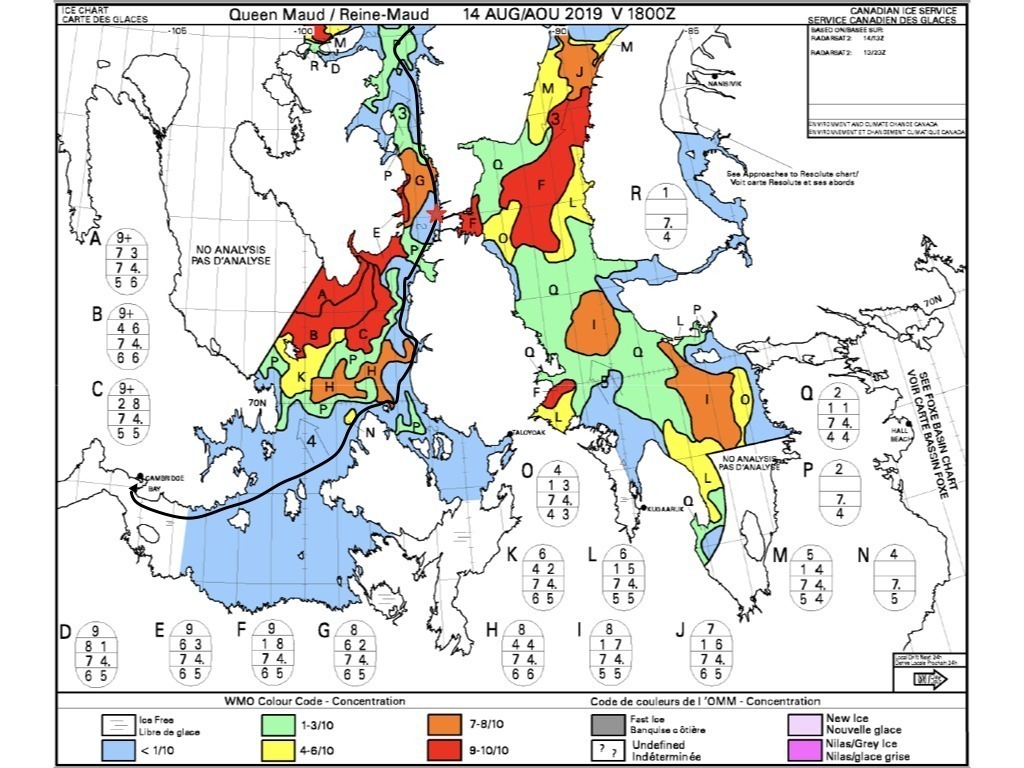

Sailing into the ice, is always a risk. Markus emphasizes that not only the present day weather and ice charts are interesting, but also the history of past winters. There are years with a very thick and wide ice belt along the coast, and years with less ice.

As for 2024, the year of CASTELLA´s journey, Marianne and Markus had to face a strong ice year: “By the end of May, the ice belt was still as wide as 60 kilometers off the coast of Tasiilaq, twice as wide as the year before!”, Markus remembers. “But luckily, by the end of June the ice charts showed a free passage to the southeast of Greenland. By the way, we had do set sails because our insurer had imposed a maximum ice-cover thickness in which only we were free to go. So we set sail.” It was July the 15th when they finally left Iceland.

"It's important not only to consult current weather and ice charts, but also to analyze the history of previous winters. Some years the pack ice stretches far along the coast, others are milder."

CASTELLA made good progress in moderate winds, but during the five days of the passage, the engine had to run for 26 hours. With daily temperatures around 8 degrees Celsius and water around 12, it was especially interesting to suddenly watch them drop significantly as the boat entered the waters of the Greenland current. From 12 to just above 4 degrees, this mighty stream brings ice-cold waters and a lot of ice from the Arctic. Exciting, especially for the marine scientist.

.JPEG)

Apart from nature, one of the most important daily routines (besides cooking) was checking the weather and adjusting tactical decisions as well as the big picture to the ever changing situation with drift ice and icebergs. CASTELLA is equipped with Starlink, which, as Markus confirms, worked spotlessly even in these high latitudes. The crew kept a close eye on the danger zones as well as the wind prediction. Keep it safe!

Other exciting things happened, which offered a rich palette of offshore-experience for the crew: A diesel filter failing, resulting in a huge spill in the engine compartment being on the more enervating side of the spectrum; some crazy changes in temperature from 4 degrees to almost sunny and “Mediterranean” conditions making the crew their head scratch and celebrating a breath of summer on deck. But then, after five days, the first mighty icebergs with Greenland´s coastline came into sight. A perfect sailor´s morning after some 650 nautical miles.

"(...) after five days, the first mighty icebergs with Greenland´s coastline came into sight. A perfect sailor´s morning after some 650 nautical miles."

"Ice can drift at 2 knots!"

About 10 nm off the entrance of Prince Christian Sound, CASTELLA reached the edge of the ice. Dense fog came up, cracking ice was heard – it became really spooky. The ice belt is an ever moving field. Growlers are almost submerged “splinters” of ice – much smaller than the big icebergs, but feared as these as well can do damage to boats and even ships. What a relief it was to be sailing with an Allures, Marianne says, because the rugged aluminum hull instilled a lot of confidence and both perceived as well as real safety.

Marianne confides, "How lucky I am to be aboard an Allures: the solid, reassuring aluminum hull provides a real sense of security, both real and felt."

The challenge: Ice isn’t sitting still, like in a computer game. It is moved by current and wind. “We’ve had to put a constant, very thorough lookout up on deck as I really did not want to test the actual material strength of our hull …” Carefully and meticulously CASTELLA moved under engine through the white sprinkled sea. Although they had up to 15 kn of AWS, sailing would have been too dangerous.

“When we reached our anchorage, my heartrate could finally drop. It was such a relief!” Which did not hold for too long, as early the next morning the screeching and scratching of an ever thickening ice layer woke up the worn-down crew. “Anchor up! Let’s leave!” Normal procedure in Greenland.

This exciting start on that day was followed by an unforgettable ride through the Prince Christian Sound in fantastic weather.

From Greenland to Nova Scotia: "New World in Sight!

CASTELLA stayed in Greenland for 3 weeks. Hopping from inlet to inlet, dropping anchor in barren, empty bays or berthing in the few settlements. When ferrying out by dinghy to the shore, the shotgun became their life insurance: Wild polar bears are a constant risk in Greenland. Happily, they had never to deal with an aggressive encounter. Nature was as jaw dropping and inspiring, as was meeting with the people. Their welcoming culture, friendliness and curiosity created many happy memories. “Sailing along Greenland and the adventures would fill a whole book”, Marianne says: It´s as wonderful as you think of it to be, but also so different from what you have in your mind.

.jpg)

“Sailing along Greenland and the adventures would fill a whole book”, Marianne says: "It´s as wonderful as you think of it to be, but also so different from what you have in your mind."

Making her way up North along the southwest coast of Greenland, CASTELLA met only very few other yachts, but made friends with many sailors. The little settlement of Narsarsuaq with not more than 130 inhabitants was the last stop: Here, international flights use to land and another crew change could be organized for the last leg: Finally, they would reach the ”new world”!

Starting the third and longest leg to Halifax on Nova Scotia, this would be the longest leg of them all. That is why they replenished their provisions as much as they could and finally set sail in Qaqortoq, the largest settlement in South Greenland, with only 3500 habitants. It is Greenland´s center for seal-produce (all of which is strictly forbidden in any case in Europe).

"...in the Labrador Sea, the crew must continue to consult the ice charts and remain on the alert for icebergs which, even in summer, drift southwards..."

CASTELLA made good progress in nice winds, averaging 6 knots SOG. Leaving the coastline of Greenland which during summer is for the most part free of ice. Leaving the fog and leftover drifting ice behind, very slowly air temperature began to rise again. Nevertheless, the crew still had to study the ice charts in the Labrador Sea and keep watch for icebergs, which also drift southwards in summer with the Labrador Current.

After five days of great sailing, the last of which was a quick close hauled upwind passage, CASTELLA´s crew saw the first signs of land: America! “It´s strange to say, but we could really smell the forest from so far ahead!”, says Markus. On a very clear day they landed in Lewisporte, Newfoundland. They stayed a few days and finally reached Halifax on August, the 17th. The crew had to spend a few days, weathering a passing Hurricane which did no harm at all, before finally arriving at the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron, America’s oldest Yacht Club – the end of an almost 4.000 miles long journey.

"It's strange to say, but you could really smell the forest from so far ahead," says Markus.

A brave ship, indeed!

What for other ships may be the “baptism in fire”, was more a “baptism in ice” for CASTELLA. Tackling such a long and challenging route is quite an undertaking. Apart from the – admittedly enervating but overall harmless – setbacks due to failing little parts, the boat more than lived up to its reputation. “She indeed is a very stable and rugged platform, instilling a feeling of real safety even into guests who have not much offshore experience”, Markus says. Marianne adds that CASTELLA has proven her storm-rigidity on many occasions since the handover in 2022.

“She indeed is a very stable and rugged platform, instilling a feeling of real safety even into guests who have not much offshore experience”, Markus says.

Being skilled sailors before and having collected hundreds and hundreds of nautical miles with CASTELLA, our customer couple confirms that the Viking Route was indeed the most challenging and exciting trip so far. After completing the Viking Route, they are once again 100% reassured about their capabilities and those of their fine, brave yacht, continuing their offshore journey with bold confidence.

To find out more about theAllures 51.9 : click here

Two solo circumnavigations, one by plane and one in allures 40.9

A sailor and airplane pilot

Harry is a true modern-day pioneer! Now aged 74 and originally from Bainbridge Island, Washington, USA, this trained engineer is passionate about aviation and sailing. Between 2011 and 2019, Harry made solo flights to all seven continents aboard a small, single-engine fiberglass aircraft. His adventures have taken him twice around the world and even over the North Pole. He recounts these experiences in his book Flying 7 Continents Solo, in which he recounts the challenges of his solo air travels.

Alongside these flights, Harry also sailed extensively, notably between Seattle and Alaska in his first sailboat named Raytrace. Then he wanted to go further, and formulated the project of once again circumnavigating the planet solo, but this time in a sailboat. And he chose a safe, maneuverable boat: an Allures 40.9, to be delivered in 2022 and christened Phywave.

He recounts these experiences in his book Flying 7 Continents Solo, in which he recounts the challenges of his solo air travels.

At least one stop on each of the 7 continents

Harry's solo voyage, which began in Norfolk in August 2022, spans over 38,000 nautical miles, more than 350 days at sea and stops in 20 countries and territories. From the icy waters of Antarctica to the sunny shores of Australia, his journey has been as varied as the continents themselves.

After his first Atlantic crossing, he stopped off in Portugal, in Lagos, to discover the wines and landscapes of the Algarve. In Africa, he stopped off in Morocco, then South Africa and Namibia on his return journey. Harry sailed along South Africa's famous Wild Coast, carried by the powerful Agulhas Current. In South America, he stopped off in Brazil, Argentina and Puerto Williams, Chile, where he was able to refuel and admire the spectacular fjords and mountains of Tierra del Fuego. Harry then crossed the dreaded Drake Passage to Antarctica, a solo feat! In Australia, after opening a new, shorter route through the Great Barrier Reef, he celebrated his Pacific crossing with a long stopover in Darwin to avoid the tropical cyclone season. In Asia, a planned one-week stopover in Lombok, Indonesia, was extended to a month, to allow time for unexpected but essential repairs to the boat's engine. After crossing the Atlantic for the third time from South Africa, Namibia and the island of St. Helena, he made his triumphant return to North America in Fort Lauderdale.

Harry's solo voyage spanned over 38,000 nautical miles, more than 350 days at sea and stopovers in 20 countries and territories. From the icy waters of Antarctica to the sunny shores of Australia, his journey was as varied as the continents themselves.

A blog to share your encounters

This circumnavigation will have tested Harry in an entirely different way. " Sailing is obviously much slower and physically demanding. But it allows a stronger immersion in the environment, a better appreciation of each destination and a connection with the international sailing community. " So, throughout his voyage, Harry has highlighted on his blog the encounters that enrich his adventures. Whether it's local fishermen, island families or other sailors and aviators, each encounter brings a human dimension to his stories. He also shares his thoughts on life, sailing and flying, emphasizing the importance of preparation, resilience and openness to the unknown.

" Sailing is obviously much slower and physically demanding. But it allows a stronger immersion in the environment, a better appreciation of each destination and a connection with the international sailing community. "

What next?

For most, such a feat would mark the end of an incredible adventure. But Harry is already planning what's next. His ambition is to bring Phywave back to Bainbridge Island via the Northwest Passage. " I've already tackled the ice in Antarctica. I hope this experience will serve me well for the Arctic challenge. " Another great challenge for Harry!

The Allures Yachting shipyard is impressed by Harry's achievement and offers him its warmest congratulations once again.

To find out more about Harry's exploits at sea and in the air, visit his website: www.phywave.com

Fou de Bassan: 3 years Around the World in Allures 51.9

" One day we'll go around the world ".

WhenDominique met Véronique, he was already sailing quite a lot. His grandfather, a naval officer, introduced him to sailing as a child. Véronique, however, is not a fan of the sport. However, before getting married, he proposed: " One day we'll sail around the world ", and she didn't say no. Professional life caught up with them, he a company director in the Paris region, she an ENT doctor. They have ties with Brittany, in North Finistère, and the sea is never far away. Dominique continues to sail a little, from time to time. In 2017/2018, he will be racing in a transatlantic race with his brother-in-law, the Transquadra. And when Dominique hands over his business in 2019, Véronique knows that it will soon be time for their departure: " It was his childhood dream, so there was a time when we had to go for it!

Dominique set out to find the ideal sailboat. He wanted it to be comfortable and safe, made of aluminum, so that Véronique could feel at ease. Big enough to welcome family on stopovers, to store water sports equipment, but above all to be easy to handle for two. And a centerboarder, to get into the Pacific atolls, would be even better. Allures Yachting has just presented the plans for its new Allures 51.9It's going to be this one!

What's more, the Grand Large Yachting group is organizing its first round-the-world rallie , the World OdysseyThey see it as an opportunity to sail even more safely, and to make new friends. But the departure takes place in September 2021, and the boat, the first in the series, will be delivered just a few weeks before the start. Three years on, Dominique is still convinced of his choice:

"I'll take the same boat again! This boat is super comfortable, super safe and easier to handle than a catamaran, especially on long crossings and in harbors.

Andapprehension disappears

" I think when you cast off, you can be a little apprehensive about the unknown. We hardly knew the boat at all. We knew we were embarking on something, without knowing exactly what it would be. Gradually, we got the hang of it. And then there's no apprehension at all. Dominique, who has always loved technique, soon knows everything about his boat, and is happy at sea and at stopovers. Véronique admits that she needed more time to adapt, and was initially happier to arrive at stopovers than to leave them. But she gained confidence and really found her pleasure in the adventure:

" I never thought I'd make it around the world so easily.

Today, she even feels a touch of personal pride, quite legitimate, at having completed this round-the-world trip with Dominique! They quickly found their rhythm on board. On the long crossings, they split the night watches in two: Véronique stays up until 2 a.m., after which Dominique takes over. Then the days are finally full: the weather, reading, cooking, " and also just the pleasure of being there, meditating as you let yourself be rocked by the wind and the waves ", says Dominique. Véronique reads a lot, the Fou de Bassan is overflowing with books. She writes a blog, and their friends and family patiently await the new articles and accompanying photos. They also enjoy receiving their families, children and grandchildren on stopovers. On some crossings, too. One of their daughters even spent 3 months on board with her children in Tahiti. And everyone met up again in South Africa for a southern Christmas party.

The pleasure of discovery

Whatmost motivated Véronique, who is very curious by nature, was discovering new cultures. Before visiting each country, she learns all she can about it: the meaning of the flag, political institutions, cultural highlights, gastronomy, the economy... Visiting so many countries in 3 years was a real passion for her. Dominique too:

" Travelling is about discovering others, meeting people, cultures and countries. I'm always fascinated by the cultures we meet.

Dominique admits that by joining the rallie World Odysseyhe was worried that he'd find himself in an overly constrained environment, and " in fact, the environment is extremely free, and the friendships you make with the other participants are really great. Sometimes we follow slightly different itineraries, we don't see each other for a month or two, and then when we do it's really nice to meet up with people we know who are going through the same thing as us ". For Véronique, it was also reassuring to sail around the world with several boats. And, just like Dominique, she appreciated the new friendships she made with people of different nationalities: " In the end, during these 3 years, we spent more time with our friends on the rallie than with our long-standing friends ashore ".

Even if it annoys them a little (because everyone asks them), we obviously asked them what their favorite ports of call had been: Véronique was astonished by Namibia and loved all the stopovers with her family. Dominique loved the trip, but if she had to pick just one stopover, the arrival at Nuku Hiva was extraordinary after 17 days at sea, and the Lau (Fiji) with its isolated islands is very endearing.

Both at sea and on land, their complementarity and complicity are obvious. While Dominique was at the origin of the project, it's clear that Véronique has also found her place in it.

" It's really an extraordinary journey, it's beyond anything I'd imagined! "

And at the rallie's closing evening in Ponta Delgada, he emotionally thanked Véronique, " his best teammate ", for the 3 years of happiness spent together on the seas around the globe.

Watch their video testimonials

ARC+ 2023 and rallie the sun islands

Full speed ahead on the Atlantic, in a flotilla

This winter, the transatlantic routes were packed with yachts in search of tropical horizons. Among the many participants in the ARC+ and Route des îles du Soleil rallies , two Allures 45.9 stood out for their marine performance and seakeeping: TENGRI and NOMAD. Two names to remember, two crews to salute.

A yacht designed to combine speed, safety and elegance

As a reminder,Allures 45.9, our first fast cruising sailboat, is the "sporty" version ofAllures 45.9 meters class sailboat) with a lifting keel a mast . Unlike the original centerboarder version centerboarder, here it is the lifting keel, with a slightly bulbous shape, that carries the ballast with a lower center of gravity. The boat gains nearly 2 tons. The mast and its Rod rigging further lighten the whole, especially at the top, making the boat even faster, and above all less sensitive to pitching and therefore even more pleasant at sea.

TENGRI: first in real life on the ARC+, ahead of the giants

On the ARC+ 2023, between Cape Verde and Grenada, Yermek ASHKENOV led TENGRI at an impressive pace:

" TENGRI really has great speed potential! We even made a peak speed of 17 knots .

.jpg)

On arrival, he was also delighted with the perfect balance between performance and safety on his Allures 45.9: " TENGRI is a great boat! Strong enough to break the ice, and fast enough to compete with high-performance yachts ". Indeed, TENGRI came in first in real time in Granada in its Class B category, leaving behind 15 boats, including 55-footers.

A glance at the finish line reveals no less than two Amel 50s, a Grand Soleil 46, an Xc 45, two Oyster 55s and a 53 or a Hallberg-Rassy 53 behind them, almost to their surprise...

NOMAD: thrills and control on the Sunshine Islands Route

On the Route des îles du soleil, Jean-Luc and Marie-Claire BRUGGEMAN, who took possession of their new boat in May, were also quick to take advantage of NOMAD's speed potential. It has to be said that Jean-Luc has a serious racing background, which is why, when it came to choosing a cruising boat for their round-the-world trip, they were looking for a safe, but above all fast yacht: theAllures 45.9 was made for them!

Accompanied by two crew members, they pushed the boat up to 16 knots on a very windy day! " Generally speaking, Marie-Claire and I had a big debate about whether I should apply the brakes at times, to encourage fishing and provisioning on board, " Jean-Luc tells us, amused... and proud. Both also told us how much they appreciated the safety and serenity provided by their boat: " to the point where we sometimes wondered if we were on the same ocean as our competitors, who were complaining about being in a washing machine. We didn't have the same feeling at all aboard NOMAD.

And at the finish in Les Saintes, out of 18 participants in the rallie, there were only 2 catamarans and a 56-foot monohull in front of them - impressive!

We sometimes wondered if we were on the same ocean as our competitors..." [...] "Some people talked about a washing machine. [...] "Some people talked about a washing machine, we felt like we were in a cocoon."

blue water cruising in aluminum: fast and reassuring

These two brilliant performances demonstrate, if proof were needed, that today's blue water cruising on an aluminum sailboat is not only safe, but also fast! Congratulations to Yermek, Jean-Luc and Marie-Claire for steering their boats so brilliantly! And thank you for sharing their adventures with us.

📊 S ee the Sun Islands 2023 rallie rankings

First Atlantic crossing for World Odyssey 500 participants

A transatlantic race forty years in the making

For many of the crews involved in the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey 500, this first Atlantic crossing was a founding moment. " We'd been dreaming of doing the Transat for almost forty years," says one sailor, moved to have finally realized this long-standing project. Twenty-one days at sea, far from any coastline, represented an unprecedented experience. "It's really a time we've never experienced before, alone on a boat for so long." These are the stories of the Allures owners, who emotionally share their experiences and learnings aboard their blue water cruising aluminum sailboat.

"We'd been dreaming of doing the Transat for almost forty years," says one sailor, thrilled to have finally made this long-standing project a reality.

Tougher conditions than expected

The image of a gentle transatlantic race under trade winds, warmth and swimming was quickly disproved. After a few days of flat calm, the crews had to contend with sustained cross seas. Weather systems forced them to lengthen the route via Cape Verde, adding almost 400 miles to the initial course.

"It wasn't the quiet transatlantic race we're sometimes told. But it was a rich experience, which taught us to adapt."

Letting go and finding your own rhythm

As the days went by, the sailors had to come to terms with a new temporality. "You start by telling yourself six days... then nine, then fifteen... and eventually time flows differently." This crossing was also an intimate ordeal for some: leaving behind children and grandchildren, accepting uncertainty, and above all learning to trust.

"To sail around the world, you have to let go of a lot of things. The sea teaches us this path to trust."

Diverse crews, a shared experience

Some sailed as a couple, faithful to their balanced life at sea, while others took on board friends and family. "Our crew was a bit of a motley crew: a mountain man who had hardly ever sailed, an experienced sailor who was new to transatlantic sailing... and yet, it all worked out really well." Ashore, families meet up with the crews, sharing Christmas or festive stopovers, while at sea the crossing remains a two-person affair, or a small, close-knit group.

"Our crew was a bit of a motley crew: a mountain man who had hardly ever sailed, an experienced sailor but a transatlantic novice... and yet everything worked out really well."

Discovering solitude at sea

In the middle of the ocean, a singular feeling sets in: that of being truly alone. "When, after days, you finally see a boat appear on the AIS screen, it's almost like a child's joy. And when you see it for real, even in the distance, it's even greater."

Sailboat reliability, a precious ally

All emphasize the importance of the boat in this experience. "We were blown away by the boat's reliability and comfort, even in rough seas"

The trimming and route choices, which at times involved trial and error, enabled us to better understand the yacht's capabilities and optimize navigation.

"We were blown away by the reliability and comfort, even in rough seas."

A key stage in a round-the-world trip

This first transatlantic race, with its unforeseen events and lessons learned, marks a founding stage of the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey 500.

Beyond the technical challenge and the miles covered, it is a human adventure that is being written, between confidence, solidarity and wonder - carried by the passionate testimonies of the Allures owners.

Watch their video testimonials here.

Life on board during the transatlantic race: reading, music, sport and DIY

A daily rhythm of multiple activities

During their Atlantic crossing as part of the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey 500, the Allures owners describe their varied and sometimes unexpected daily lives. Reading takes center stage, providing an opportunity to catch up on the reading time put aside before departure. But the activities on board don't stop there: board games every evening, writing and recording songs as a family, moments of sharing that make the crossing unique.

Sport and well-being, even at sea

Between sunrise yoga sessions, exercises adapted to the movements of the monohull and swimming in the open sea, the crews know how to keep active. Snorkeling, paddleboarding and inflatable kayaking make the most of stopovers and navigation breaks.

DIY, fishing and discovery

As every sailor knows, a sailboat requires constant attention. Small repairs and adjustments punctuate the days, even aboard a new boat. Some crews have also tried their hand at deep-sea fishing, sometimes successfully, sometimes with the bitterness of losing their lures to overpowering tuna or barracuda. "We still have a lot to learn, but it's a great lesson in the sea," they confide.

"We still have a lot to learn, but it's a great lesson in the sea," they confide.

A rich and creative journey

Beyond the sailing, this transatlantic race was an opportunity to share human and creative experiences, strengthening the bond between crew members and families. The Allures owners remind us that on board, the most important thing is not only to move forward, but also to savor every moment.

Watch their video testimonials here.

Geneviève and Etienne, aboard Loly: a round-the-world trip in Allures 45.9

A tribute and a family story

The name of their sailboat, Loly, was not chosen at random. It echoes the nickname of Etienne's father, the man who instilled in him a love of sailing. "It's a way of paying tribute to him," she explains.

A boat designed to go far

From the outset, Étienne had a clear objective: to sail with confidence on a robust, seaworthy yacht. With their Allures 45.9, the couple found the perfect balance between solidity, performance and comfort.

"We've just crossed the Atlantic, and I've never felt insecure," says Geneviève.

Their childhood dream comes true: to explore distant horizons, with the certainty of being well protected, whatever the conditions.

A family and human adventure

Beyond the sailing, this adventure is also a story of family and sharing. Three of their children joined them for an unforgettable crossing. Musical moments improvised on board, laughter and memories engraved: Loly has become a real place of life and transmission.

"You have to let go of a lot to go around the world," confides Geneviève. "But life itself is an adventure, and you have to know how to throw yourself into it."

The choice of Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey

When they heard about the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey project, Geneviève and Étienne didn't hesitate for long. For them, this rallie was the ideal opportunity: to set off far away, but with the security of a group and the emulation of a community.

"Travelling together is extraordinary. We remain free, but we create a family. The bonds we've forged are precious," says Geneviève.

A rhythm of life at sea

On board, life is simply organized: yoga at sunrise, daily swims, sailing in rhythm with the wind and the sea. The adventure is not only maritime, it's also interior: an art of living, as close as possible to what's essential.

A shared adventure

For Geneviève and Étienne, it's clear that they might never have undertaken a circumnavigation on their own. But together, and surrounded by the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey flotilla, they feel carried, inspired and transformed.

Watch their video testimonials here.

Panama Canal: a key stage in the World Odyssey 500

Gathering at Shelter Bay Marina

At the end of February, the fleet of the Grand Large Yachting World Odyssey 500 gathered in the peaceful marina of Shelter Bay, facing the large city of Colón and its 90,000 inhabitants, gateway to the Panama Canal. Let's hear from Victor, Event Manager on the rallie. We spoke to Victor by telephone from Panama airport, where he was about to set sail for the Galapagos:

"The boats stayed at Shelter Bay Marina for between a week for the latest arrivals and 10 days for the first ones on site, such as Chamagui 2. There, the bulk of their activity consisted of preparation for crossing the canal. This included measuring and registering the boats with the canal authorities for administrative purposes, and technical preparation for passing through the locks, which require four people per boat. After crossing the Caribbean Sea, the crews took advantage of these moments to make supplies, fill up with diesel, and then prepare for the departure to cross the canal".

The Panama Canal, a piece of history

As early as 1534, Charles V ordered a study to be carried out on the Panama Canal. This would save Spanish ships from having to sail around South America via Cape Horn. The King of Spain and the German Emperor, thanks to the accounts of the conquistadors, had identified the Isthmus of Panama and its 80 km of coastline as the narrowest passage in the whole of Central America.The construction of the canal, begun by the French in 1881 and completed by the Americans in 1914, was fraught with difficulties. Nearly 6,000 people died on the site, for reasons ranging from malaria to earthquakes and landslides... The history of the site is also marked by a huge scandal in the 1890s. Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had "paternized" the Suez Canal 40 years earlier, remained convinced that crossing the isthmus could be done without building locks - but he was wrong, and led many gullible shareholders into this error.Rich in this eventful history, the Panama Canal today represents a strategic point for world maritime trade. Every year, some 14,000 ships pass through it - mainly merchant vessels, but also pleasure yachts such as the rallie.

Around 14,000 ships pass through the Panama Canal every year - mainly commercial vessels, but also pleasure yachts such as the rallie.

The Pacific, a great moment for all

Victor describes crossing the canal as follows: "We split into two groups of 12 boats. Let's take the first group, for example, which left mid-afternoon on a Tuesday. It crossed the first three upstream locks in the late afternoon. Known as the "Atlantic locks", they involve an ascent of around 30 meters. The boats then found themselves on Lake Gatum, where they tied up to the buoy in pairs until the following morning." On the second passage, Chamagui, Chaps, Bluway and Salavida found themselves moored together at the buoy on Lake Gatum: this provided one of the beautiful images of this Panama Canal crossing. Victor continues: "On Wednesday, 10am, departure for the second section of the canal, crossing Lake Gatum until reaching the two downstream locks of Pedro Miguel and Miraflorès at around 4pm.

Here again, the gradient drops a few dozen meters, offering a unique view of the Pacific Ocean below. Crossing this section takes a few hours, and by 8pm everyone had crossed the Bridge of the Americas into the Pacific. A great moment!

Then, because of the requirement to have 4 "handliners" on board in addition to the captain, we organized a shuttle to bring crew members from the first team back to Shelter Bay, so that they could help the boats taking part in the second passage. This was a great opportunity for the crews to get to know each other and strengthen their mutual support. It was important to stay focused, however, because once the boats, which come in as a pair, have entered the swirl of locks, you can't miss your mooring knot!

Theboats crossed the canal unharmed. Everyone gathered at the Playita de Amador marina, on a peninsula southwest of the canal exit. It was time to celebrate the passage into the Pacific, a first for almost all the crew members present. Now it's time to set course for the Galapagos, 900 miles away, heading south-west!

World Odyssey 500 - Stopover in Martinique

Clement weather

It may seem surprising to cross the Atlantic Ocean under sail from east to west in the middle of winter, but this is the ideal time of year to sail from Europe to the West Indies. Once you've reached the inter-tropical zone, which in the North Atlantic begins around Cape Verde, there are no more lows or high pressure systems, but rather a regular wind regime that ensures fast downwind sailing for the boat and comfortable temperature and humidity conditions for the crew. What better way to gain transatlantic sailing experience?

It may seem surprising to sail across the Atlantic Ocean from east to west in the middle of winter, but it's the ideal time of year to reach the West Indies from Europe.

A technical stopover

The boats arrived in mid-January at the marina in Le Marin, Martinique, and were welcomed as they should have been, with the organization taking charge of their mooring, carrying out the maintenance work required for this technical stopover, and taking part in a social program that helped to bond the members of this sailors' collective. As for the technical stopover, the aim was to carry out the necessary checks after several weeks at sea: running and standing rigging, electronics, engines, fluid management, sail condition - nothing was left to chance for the Allures yachts, whose entire current range - 40.9, 45.9 and 51.9 - is taking part in the rallie.

.jpg)

"The advantage of this technical stopover is that we knew exactly what was in store for us," says Vincent Mauger, Grand Large Services Manche manager, "all the boats needed a check-up, which is perfectly normal after a transatlantic race. We knew on a case-by-case basis what spare parts to bring, and what intervention to plan. This level of preparation gave real meaning to our presence in Martinique, where two of us - carpenter Yann and myself - came specially from the Cherbourg yard. And the owners were delighted with our presence, as evidenced by the warm thanks they expressed to us and the small party given in our honor when we left".

.jpg)

A friendly stopover

In terms of conviviality, as soon as they arrived, the crews were offered a welcome aperitif aboard a floating restaurant in Le Marin. The following day, they visited Habitation Clément, an emblematic rum house in Le François, which, with its rich heritage and botanical riches, represents an unparalleled introduction to Creole culture. On Friday, everyone could take part in a picnic on the beach at Islet Chevalier, where volleyball teams were formed in good spirits. And these opportunities for exchange, whether initiated by the organizers or the participants themselves - and there were many more of them - enabled the participants to get to know each other better.

.jpg)

"The general atmosphere was excellent among all the participants," adds Vincent, "andany uncertainties felt in Tenerife before the big crossing were completely dispelled. I'm referring to some people's doubts about their ability, as sailors, to carry out this navigation lasting several weeks, as well as various questions about the potential, behavior and reliability of their boat." As for any divisions - between monohull and multihulls, for example - they were neatly swept away, and made way for one and the same family, that of the happy participants in a memorable and, for many, unique sailing experience.

"The general atmosphere was excellent among all participants".

.jpg)

There's no doubt that the reassuring presence of the crews dispatched by the shipyards, as well as the level of availability displayed by the members of the organization, contributed to this success. The content of the briefing devoted to the fourth leg to Panama confirmed this: when you leave the Atlantic to enter the unknown Pacific, there are few certainties that can be taken for granted, other than that of mutual aid and conviviality at all times between the members of this great collective adventure.

Finally, the flotilla start on January 22, like the start of a regatta between Le Marin and Sainte-Anne, not only confirmed all this, but also confirmed that the boats were sailing well together on long, sunny tacks. It just goes to show that conviviality and good humour can be perfectly combined with a dash of performance!

.jpg)

A dream come true: theAllures 45.9 takes you on a voyage of discovery.

After years of cruising the Mediterranean on a composite sailboat, this passionate sailing couple have taken the next step: the big departure. Their choice? A Allures 45.9. An aluminum centerboarder , designed for adventure and serenity. For them, the equation was simple: solidity, comfort and autonomy. Aluminum for safety, lifting keel to explore more freely, and an elegant hull that transforms every mile traveled into pure pleasure.

Today, freshly retired, they are setting sail for a round-the-world voyage through the trade winds, following Jimmy Cornell's legendary route. It's a carefully thought-out, well-prepared project, supported by the Grand Large Yachting Group's Services division, so they can set off well-equipped.

Watch their inspiring video testimonials below: the story of a dream come true.

From regatta to horizon: Allan and Linda's journey to blue water cruising

Runners before cruisers

For Allan, competitive sailing was a big part of his life from an early age, as he studied in Scotland and then in London for the first few years of his career. Linda's entry into the sport came when they spent time sailing together in Menorca, first on Lasers, then on 420s, before returning to London where they raced double-handed on lightweight dinghies for the rest of their working lives.

"Linda and I raced dinghies from 1985 to 2012. In southwest London, one of the big clubs had a large Fireball fleet, which attracted us to this single trapeze performance double-handed dinghy. We sailed Fireballs for several years until asymmetric spinnaker skiffs came on the market. Then we joined with other club members to buy an ISO when this model came out, and then an RS500, whose class we joined. We even organized the RS500 World Championships in 2011, the year before the 2012 Olympics, on the very Weymouth site that would host the Olympic sailing events! "

We had no idea that people were living on sailboats year-round living sailboats that this was a tangible option that could be applied to us.

.jpg)

A new tactical option

"We started chartering boats in flotillas in the 90s, mainly in the Mediterranean, a little in the Caribbean. A few years before we retired, in 2013, we were in Greece on a flotilla vacation looking for post-retirement ideas, and the captain of the flotilla kept talking about these "privateers" who lived constantly on the move. We had no idea that people lived on inhabitable sailboats year-round sailboats that it was a tangible option that could be applied to us. Until then, our lives had been organized in a certain way. We were actively involved in dinghy racing and occasionally went on cruising vacations, but above all we were building and pursuing our respective careers: a very different mindset ," explains Linda. It wasn't long before they decided to take to the seas for their retirement!

The approach to the starting line

Whenthey stopped working, they quickly and decisively traded in their 14-foot RS500 for a 41-foot blue water cruising sailboat (christened Touch of Grey) on which they lived for over 5 years and sailed 23,500 miles,"to test life". Adopting a new mindset as cruisers, they moved from day cruising to coastal cruising, then on to an Atlantic crossing and an East Coast cruise that took them all the way to Nova Scotia.

"We confirmed our embrace of the lifestyle that cruising represents, but we also quickly learned the limitations of the 41-foot production boat for extended cruising, blue water cruising and offshore sailing. We started looking for a new boat in 2017 and visited the Annapolis boat show. Allures wasn't on our radar, but we came away both unimpressed by the boat we had in mind, and positively marked by theAllures 45.9 : let's just say it hit the nail on the head! There was no real competition.

" TheAllures 45.9 felt more spacious and modern, and was well laid out according to principles we'd understood were important to us over the previous 5 years of cruising."

The Allures offered good visibility from the saloon and plenty of light, a practical central table, and a work/technical room. We appreciated being able to get into bed facing the right way, without having to climb over and turn around. The forward locker was spacious, and we were attracted by a more flexible sail configuration for better performance. Finally, with its aft davit and davit crane,Allures 45.9 designed to accommodate solar panels could lift and carrydinghy... we were moving from a weekend boat to a quality offshore cruising boat, truly designed for life at sea! We placed our order for the Allures 45.9 in April 2018, and Stravaig was launched in June 2019.

Taking advantage of the laughing stock

"After the boat was delivered to the yard in Cherbourg, our plan had always been to get to know our boat by means of rather short sailings, coastal cruises or to relatively nearby destinations. Very quickly, we also steered clear of the CoviD-19. In March 2020, we were on the boat in the Canary Islands when containment was declared in Spain; yet we had planned to spend the summer in Norway until that country closed its maritime borders. In the end, we headed for the Channel Islands, where we were lucky enough to obtain local boat status for the summer. We were quarantined for 15 days in Guernsey, but then spent two months enjoying the Channel Islands in a unique and exclusive way, as there was no tourism for the entire summer of 2020."

After sailing the Channel Islands, getting to know the boat and fine-tuning it, Allan and Linda were well prepared for the Atlantic crossing and beyond. The Stravaig blog begins here, with the story of their 10-day voyage from Guernsey to Lanzarote!

Double-handed offshore sailing

Fromdinghy racing to theAllures 45.9, the plan has always been to sail double-handed! In January 2021, Allan and Linda set sail from Lanzarote to Granada. They share some of their favorite moments and insightfully blog about topics such as weather routing and boat handling, which are recurrent in this logbook, particularly intended for sharing the adventure with their loved ones. Weather itinerary -"Our route, from Lanzarote to Granada" by Allan: "As far as conditions were concerned, we weren't in anything extreme, not prolonged extremes in time, anyway. When we crossed the Atlantic in 2016, it was a bit grueling with 3 people, but this time we felt pretty comfortable, just the two of us alone on board. Conditions were similar, in fact tougher towards the start of the crossing, but the boat handles well when the weather turns bad, and we never felt it get out of hand.

Our sailing plan is quite flexible, with a wide range of options designed to adapt to conditions.

We love the thrill of sailing with the Blue Water Runner (a furling downwind sail that can be deployed as a scissor or single gennaker), which, at 150 meters , is three times larger than our mainsail Another thrill was when, between days 10 and 11, we crossed paths with Charlie Dalin in the Vendée Globe less than a mile away and communicated with him by radio. You might wonder whether he inspired our competitive spirit or whether we received good weather advice, because we then recorded two consecutive days of records!" Allan pointed out.

The rest of the Transatlantic log details the constant balancing act that is offshore sailing. In all this work, there is also fulfillment and deep pleasure; through the changes in weather and sail, the balance between manual steering and autopilot, the interaction of the boat's systems, an impressively high quality food program, not forgetting knowing when to rest, the need to take breaks to admire the scenery and appreciate unique encounters with nature.

Steering by night

"It was only 7pm, but it was already dark, and the wind was fairly steady in direction, but gusty. The Blue Water Runner was out to starboard in asymmetric format. As I prepared to take the helm, I realized it had been a long time since I'd steered in the dark. (In fact, Allan reminded me later that although we did weeks of night sailing on Stravaig, we didn't really do any night steering, so the last time I did was a year and a half ago.) I couldn't see the sail, the sky was black and the instrument display had been reduced for the night and was difficult to read. I spent ten minutes swiveling: the wheel was over-corrected, the sail was constantly sagging and the boat was swinging 40 degrees or more to one side... Then, just before I lost my temper, I understood the principle. As we discovered during our daytime sailing, this enormous sail requires surprisingly delicate handling. I began to hold the helm in the center and bring the boat back to windward a few degrees at a time. All became calm and she (and I) settled into the rhythm of the night. "All is well. Linda - Jan 3, 2021, Lanzarote to Granada day 14.

Thejourney and the destination - on a loop!

The couple spent the spring of 2021 scouring the islands, scuba diving and snorkeling in the turquoise waters of the Caribbean. Following a seasonal migration of sorts, they gradually made their way north to the U.S. East Coast, while making plans for next season's magnificent sailing grounds: the Bahamas!

An extraordinary food program

"On Stravaig, I think we eat quite differently from other people. I like to cook, we eat in a contemporary way, mainly raw food. I've learned to work around the difficulties of cooking at sea, and even then we eat very well. One of the interesting things about sailing to other countries is finding new ingredients, but also working with limited ingredients and finding healthy and delicious food, being creative."

Professional writer and editor, Linda takes cooking to the next level on theAllures 45.9 Stravaig!"On a crossing, we tend to eat less (apart from snacking during quarters) and have found that we prefer simpler dishes. However, for our wedding anniversary, Linda went above and beyond to prepare something very special for us: pan-fried brill fillets in Guernsey butter, accompanied by a salad of fennel, zucchini and red onion with a lime and orange vinaigrette. One word to describe it: Brilliant. For dessert, we each had a vegan dessert from a trendy brand. I have no idea what it was free of (gluten perhaps, but certainly not sugar) and especially what it wasn't free of, the brand in question being so dominant on the packaging that everything else was recorded in type too small to read. Not as brilliant as Linda's dish."

Discover "Stravaig'n the Blue", Allan and Linda's blog, by clicking here.

Stravaig v. [Scotland]: to wander, wander aimlessly; to cross, go up and down (a place).

Allures 45.9 in New Zealand: an enchanted interlude at the end of the world

This picture gallery is the story of a meeting. On the one hand, English sailors Julian and Patricia from Herefordshire, who have been cruising in New Zealand for over a year aboard A Capella of Belfast, their Allures 45.9. We met them at the end of 2019, as they were preparing to sail to the Samoan Islands.

Stranded in New Zealand waters due to sanitary restrictions, with no way of getting their yacht back to Dover, they had considered a radical solution: contact Allures to sell their boat in Auckland... and order a new one in Europe! In the end, reason prevailed over impulse: A Capella was transported by cargo ship to Europe in March 2021.

On the other side, Gilles Martin-Raget, a leading figure in sailing photography, based in Marseille but present in Auckland for the 36th America's Cup. Between the opening of the village in December 2020 and the closing ceremony in March 2021, he will be intensively documenting this great celebration of international yachting, enriching his site with an impressive gallery.

At the beginning of March, the paths of Julian, Patricia and Gilles crossed around Kawau Island. Located in the Gulf of Hauraki, 40 km north of Auckland, the island is nicknamed "the island of 100 pontoons" for its near-absence of roads. Its rare biodiversity and landscapes reminiscent of Brittany, Provence or the far reaches of the Pacific make it an exceptional setting.

This inspiring natural setting becomes the stage for a spontaneous photo shoot, capturing the elegance of the yacht and the freedom of its owners. TheAllures 45.9 is revealed in all its beauty: an aluminumcenterboarder designed to fully experience those other places that awaken the soul.

Discover this enchanted interlude, in pictures.

From Lake Geneva to Cape Horn

My name is Julian, and I'm the owner ofAllures 51.9 #3. Half Argentinean and half Italian, I was born in Argentina and lived there for 37 years, until my wife Daniela and my children and I moved to Switzerland 7 years ago.

I sailed all my youth, starting out on dinghies when I was a kid, then moving on to bigger boats, and gradually I got into racing and even ocean racing. Then I got married, and had children, but when they were small it was complicated, even I didn't feel like sailing at the time, I thought more about being with them at home and so I stopped sailing altogether. When we moved to Switzerland, the first thing I did was to go and see a cruising school, with the aim of getting a sailing licence on Lake Geneva, but I saw that it had become so complicated in terms of administration and safety that I decided to give up.

Back to basics

But then, with this coronavirus thing, there was a combination of things. The first had to do with an Argentinian friend of mine, who had also been living in Switzerland for 5 years, and who then said to me "it's time to do something; let's take the motorboat license together because, to sail, you need a berth, and that's really very difficult here, with a waiting list of over 10 years". He goes on to say: "But if you buy a motorboat, it's possible, there's a private marina in such and such a place, and if you buy the boat from them, they'll offer you a berth". I don't really like motorboating, but it was a way of getting back on the water, and I was persuaded. I started taking courses, to relearn what I already knew, but this time in French and with local peculiarities to integrate at the same time. But very quickly, I said to myself "motorboats are great for getting your feet on the water, but they're not for me". So I bought a Laser, I'd had one before in Argentina, and that enabled me to start sailing again for real, and in a way get back to basics.

Looking out over the ocean

A few months later, the first wave of the coronavirus was gone and we went on vacation to Cadiz, Spain. I remember, on the beach, by the Atlantic, which has this special color, the same one you see on the Argentine side and which I find very different from the Mediterranean. I'm no expert, but I find there's a really different energy. And so, looking at the ocean, I remembered all my dreams when I was young. My wife Daniela came along and said, "Do you remember when we first met, you wanted to sail around the world? I remembered, of course, and said to her: "Yes, of course, and I think the time has come... The children have grown up, and this coronavirus shows us that we shouldn't take anything for granted in life". And then my wife replies: "It's OK with me, let's go"! That same day, I call another Argentinian friend, who lives in Argentina, and who I've known for over 20 years. I tell him all about it, and say "Santi, I'm looking for a boat, and I've been looking at this and that model". He replies, "Stop it! I've been looking for information on the boat I need for two years, and I've been investigating it for months. I've still got a few questions, but if you want, limit yourself to this, this and this", and then he gives me the names of three models built by European shipyards.

.jpg)

A thoughtful choice

I wanted a bigger boat, Santi wanted a smaller one; he was looking for a sailboat with a maximum length of 46-47 feet, I was aiming for a 60-footer. He said, "No, 60 feet is too big for you; you'll be sailing a lot alone or as a couple, so you'll have to choose a smaller model". My friend shared with me the fruit of his research; I had done mine, which was much more limited, and we put it all together, then made a "short-list". I wanted an aluminum boat, but in my memory, all the aluminum boats I'd seen in Argentina were ugly, square-hulled and poorly maintained. I wanted a pretty, safe, high-performance boat... and that's when Santiago said to me, "You need to look at the production of the Allures shipyard". I'm talking about mid to late July 2020. We did a lot of videoconferencing with Santiago. I said to him: "Let's go, I want to act, I don't want to wait". He says, "No, be patient, we need another two years". And I said, "Oh no, it's now or never".

"When we visited the Allures yard, we immediately saw the performance, the quality and the professionalism."

A strong and rapid decision

We came to Cherbourg with my wife at the end of August 2020: we had planned to also visit another construction site in England. As the possibility of crossing the border from Switzerland was limited, we made the trip by car, as we didn't want to take a plane. When we visited the Allures shipyard, we immediately saw the performance, quality and professionalism all around us. We also received an excellent welcome, and when we saw the way you treat the boats, the equipment, the skill... all this played a part in our decision. What's more, we didn't even look at the other shipyards we'd identified before! I had the experience of having built a boat in Argentina, and the word professionalism doesn't apply there, at least not with the yard in question, but unfortunately I'd say that's the case with almost all the yards in the country. They're often family-run, which is great, and I've got nothing against that, but where the first generation does things with a lot of conscience and effort, we see that too often the second generation burns everything, and in what they burn, there's your money and also, alas, quality. I've had a lot of quality problems.

.jpg)

The promise of future emotions

Coming here, I fell in love with this compromise between aluminum, the way this material is treated, the elegance of the boat, the shaped hull design, all of it. We signed the contract the day after we came, so it didn't take long.

"The promise of this boat, when I see myself on board, is to be able to realize my dreams."

The promise of this boat, when I see myself on board, is to be able to make my dreams come true. Our plans are, starting in the spring of 2022, and for the first year, to sail the Mediterranean, to take the time to get to know each other and fall in love with each other, ourselves and the boat. Then, in December 2023, we'll cross the Atlantic, and from there, once we're in the Caribbean, we'll have two options. The first is to cross the Panama Canal and sail around the Pacific, and then we'll see. The second option, which is unsurprisingly the one I prefer, is to head south along the Brazilian coast, towards Argentina. The arrival in Buenos Aires with my boat will be a highlight. After that, I'd like to sail down to Patagonia, go to the Falklands, a place I've wanted to visit all my life (for us it's the Falklands, not the Falklands!) and of course round Cape Horn, to tick that box. After that, we'll see: we'll either sail up the Atlantic or into the Pacific, probably via the Chilean canals. Nothing is set in stone, as we're talking about several years here, but one thing's for sure: it's going to be a very emotional program for us!

A beautiful story of friendship

When we told Santi that we'd signed the contract with Allures Yachting, he felt the pressure: we pushed him a little; I actually think that he didn't really need to be pushed, but that, coming from us, he wanted to, it was a way for him to see the story through, which is also a shared story. And so we made a promise to sail together, to cross the Atlantic on two boats, side by side. There's an emotional side to it, but also a comforting, reassuring aspect, because he's a really good sailor. There are a lot of people I'd like to do important things with in my life. But there aren't many who, like Santiago, both fit into this category and, at the same time, are good sailors.

That's the whole story, and I agree that it's also a beautiful story of friendship.

The Allures 44 Opale has crossed the Northwest Passage : 5/5 - From the Arctic to Antarctica

Between sail and motor, which mode of propulsion prevails on this route?

"For this crossing of the Northwest Passage carried out in August 2019, we sailed 90% of the time under sail between Saint-Pierre et Miquelon and Paamiut in Greenland, 50% of the time under sail along the Greenland coast, 70% under sail between Upernavik (Greenland) and Pond Inlet (Nunavut), then 90% under motor from Pond Inlet to Cambridge Bay, where we were in the ice anyway. Then another 50% by motor from Cambridge Bay to Tuktoyaktuk, then 80% by motor from Tuktoyaktuk to Nome (see map below). In fact, on this last section, either there's a lot of wind, in which case we take shelter in an anchorage, or there's no wind, and we make headway at 2 knots with the current against us, or we put the engine on so as not to arrive too late in the season in the Bering Sea. But we knew that before we set off, and we had to accept it, otherwise we wouldn't go.

It is very important to have significant reserves on board, to be able to win the next point if reserves are lacking at a given stage.

Then, in the Bering Sea, from Nome to Sand Point, we sailed all the way, with quite a few lows. All in all, that represents around 70 to 80% of motorized sailing over the whole course." So, of course, it's essential to have a high level of energy autonomy on board. This is achieved by means of gas cylinders whose standards and characteristics - it should be noted - differ considerably from one part of the route to another, but also and above all by being able to store large reserves of fuel on board: "One year, there may even be no diesel available at a refuelling point on the route, because the supply boat has not passed, and so it's very important to have significant reserves on board, to be able to reach the next point if reserves are lacking at a given stage. In fact, oil tanks are the first thing you see when you arrive in these towns and villages, both in Greenland and Nunavut."

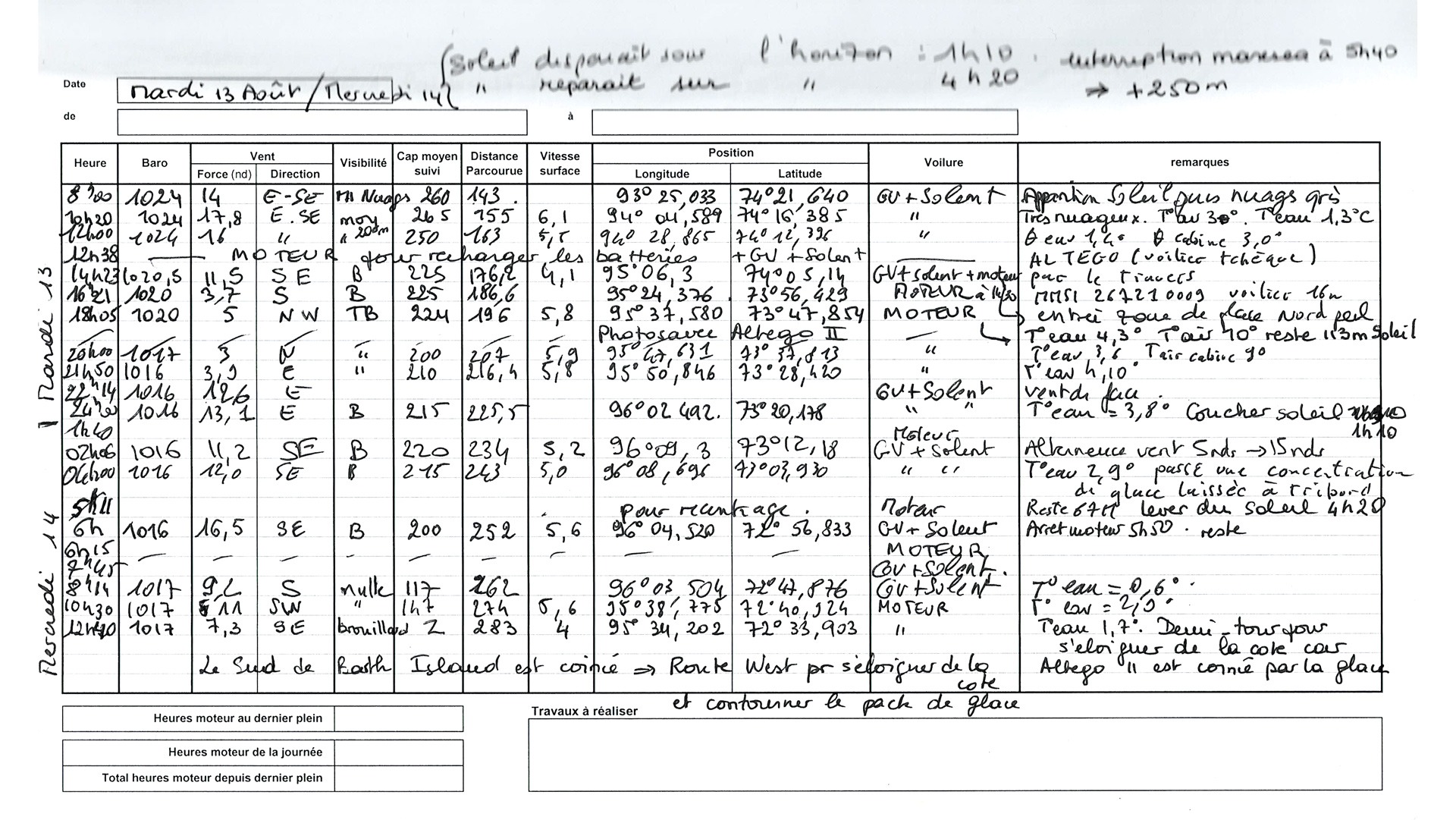

Opale logbook overview

Therelative importance of engine-driven navigation is confirmed by Opale's logbook, which is highly instructive in many respects. The information scribbled there with precision by the crew touches on everything from life on board to weather conditions, ice observations, the effect of the tides, the daily amount of sunshine, and the adventures of friendly yachts encountered along the way.

The logbook entry dated August 13, 2019 (reproduced below) mentions winds varying greatly in strength and direction, from 3 to 17 knots, but also a speed of 4 to 6 knots, achieved indifferently under mainsail solent jib under motor. There is also news of a friendly boat, Altego II, a sturdy 16-meter steel keelboat registered in Slovakia and skippered by Czech circumnavigator Jiří Denk, with whom a photo shoot is first carried out. Later in the day, we learn that the sailboat is blocked by ice, prompting Opale to write the note "Turn around to move away from the coast because Altego II is blocked by ice." The water temperature readings, taken at regular intervals every two hours, show a continuous drop, a sign of the proximity of the ice. The account of this day spent heading south in the strait between Prince of Wales Island to the west and Somerset Island to the east, between 74° and 72° N, ends with a laconic assessment full of common sense: "The south of Barth Island is blocked > Heading west to get away from the coast and bypass the ice pack."

Some happy memories?

Of course, I'll always remember the good times spent with the crew, discovering an exceptional territory and environment together. There were two of us on board with Bénédicte as far as St Pierre et Miquelon. Then, from St Pierre to Nuuk, four friends joined us, so there were six of us on board. Then in Nuuk, three of these friends left, the second watch leader stayed, and three other crew members arrived, including my daughter Claire. We had to let a crew member go in Pond Inlet, as he couldn't risk being late for work reasons, and so there were five of us from Pond Inlet to Nome, where most of the crew left again, and then on the Nome - Sand Point leg, there were two of us again with Bénédicte.

Anotherpoint was the strong bond created with the crews of friendly boats, with a very pleasant sense of mutual aid, based on just-in-time information sharing: this state of mind and this constant solidarity had a real value for us, as much for the safety of all as for the pleasure of exchange, as for example with the crews of Altego II, Morgane, Breskell and also Alioth who left his boat at Sand Point like us.The landscapes also left a strong impression on us, especially in the areas where the coastline is the most jagged, and we were able to enjoy them in the special light of the Arctic summer. In fact, I was able to capture quite a few scenes, even with my cell phone, whose photographic quality pleasantly surprised me. Incidentally, unlike Altego II and Breksell, I didn't have a drone to film Opale in these magnificent landscapes, but I've since acquired one.

Bear in mind that it's best to arrive in Alaska (Aleutian Islands) in the second half of September at the latest, as the weather in the Bering Sea can be very difficult thereafter.

Finally, the silence, the wide open spaces, the feeling of immensity all around, are without doubt the strongest memories we brought back from this crossing.The real interest in terms of navigation lies essentially on the Greenland coast, which is the most extraordinary for its landscapes, making it worth the trip in itself. Navigation and scenery are also very interesting in Nunavut, i.e. on the first part of the Northwest Passage itself, between Lancaster Sound and Cambridge Bay, as far as Gjøa Haven. After that, the north coast of Alaska, between Cambridge Bay and Nome, is rather flat, even uninteresting, with lots of headwinds and featureless landscapes, and therefore few prospects in terms of visual emotion and, moreover, a certain paucity of stopovers. This is why, from the point of view of the interest of navigation itself, it is important to plan, as we said earlier, a fairly broad general calendar for the expedition, which will enable us to position ourselves sufficiently far in advance, both to take full advantage of the Greenland coastline, which really deserves it and can be a goal in itself, and to be sure of being in the zone at the right time, i.e. from the end of July, with the hope of actually crossing the hard zone around mid-August. Bear in mind that it's best to arrive in Alaska (Aleutian Islands) no later than the second half of September, as the weather in the Bering Sea can be very difficult after that.

And to conclude?

Marcand Bénédicte provide further proof that it is possible for yachtsmen to triumph aboard their sailboat over the Northwest Passage, a route shrouded in myth, a fertile factor in the maritime imagination at the same time as being guilty of a number of tragedies. It's also a chance to prove wrong those wise men of antiquity who, like Virgil, saw in the northern confines marked by the "ultimate lands" of "Ultima Thule" (a name taken up by Jean Malaurie), the limits of the man-made world, beyond which the unknown reigned, and whose mere evocation still today opens up an immense territory of dreams.

This success has not convinced Marc and Bénédicte that they have joined an elite caste, a club of "happy few" who have achieved unrivalled feats. As Marc Pédeau made clear during a presentation on this voyage in December 2019 to the community of owners of sailboats built by the Grand Large Yachting group: he is here to pass on and share his experience in all simplicity, and far be it from him to pose as a lesson-giver who would benefit in any way from his considerable experience of Arctic sailing.

It would be just as wrong to think that Marc and Bénédicte's attraction to the Septentrion (1) is exclusive.

Thus, this crossing of the North-West Passage was part of a navigation with a much broader scope, as expressed by Marc in October 2019 in an e-mail to Grand Large Services, the entity specializing in services for sailors, notably in charge of supporting customers of the Allures Yachting shipyard :

"Over a period of 15 months, we will have reached Cape Verde (via Galicia, Portugal, Madeira, the Canaries), crossed the Atlantic between Cape Verde and Martinique, sailed the Caribbean islands, visited Cuba, then reached the USA via the Bahamas, sailed up the west coast of the USA via New York, sailed through Maine, Nova Scotia, Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, Newfoundland, then Greenland before completing the Northwest Passage: a total of 16,000 miles". The message concludes: "I'd also like to thank you for your help and responsiveness at various stages of the project: sending equipment, advice, and working on the possibility of fitting a propeller protection for the ice (which we didn't install in the end)".

Likewise, Marc and Bénédicte's next sailing project has already been established, and it involves a clear departure from the Far North, although it is currently being constantly postponed due to a health crisis, with the result thatOpale, at the time of writing, was still stuck at Sand Point. This future experience can be summed up in a few words and a lot of miles: starting from Alaska, which they plan to cover in great detail, they will then be able to sail along the American West Coast and, from San Francisco, aim for Mexico, Polynesia and New Zealand. From there, they'll cross the South Pacific to Patagonia and the Antarctic Peninsula.

It's hardly surprising to find Antarctica high on Marc and Bénédicte's list of destinations aboard their Allures 44. For this white continent, even reduced to the tongue of land that is the Antarctic Peninsula facing Patagonia, accumulates almost mythical references in the imagination of every sailor - real or dreamt. This magic of the Deep South is particularly evident in books, from the account of Ernest Shackleton and his crew's odyssey aboard theEndurance between 1911 and 1914, to the pages of Gérard Poncet and Jérôme Janichon who, aboard the famous Damien, set out in 1969 on a 55,000-mile voyage more concerned with personal accomplishment than sporting performance, eschewing any heroic aims in the image of their contemporary Bernard Moitessier. These same Poncet and Janichon were the first modern sailors to cover a range of latitudes from 80° North to 68° South, and aficionados were delighted to see them again in La Rochelle, alongside their restored Damien, at the latest Grand Pavois, in September 2019, as Opale sailed to Sand Point, Alaska.

Whether extreme latitudes are southern or northern, they are endowed with an exceptional power of attraction. The sea spray of the open ocean, the dream of the poles and the infinitely varied nuances of ice, though endangered everywhere, are a perfect match. Many thanks to Marc Pédeau and Bénédicte Michel for taking us there, sharing with us this story and these images, which make a splendid contribution to enriching our imagination of blue water cruising.

(1) Septentrion: Latin designation referring to the "seven oxen" - septem triones - which, in ancient Roman tradition, formed the circumpolar constellation of the northern hemisphere, now known as the Great Bear. Source : https://fr.wiktionary.org/wiki/septentrion

Find here all the articles of this series "The Allures 44 Opale has crossed the Northwest Passage"

The Allures 44 Opale has crossed the North-West Passage : 4/5 - The notion of risk in navigation

What were the main navigation difficulties encountered?

It soon becomes apparent that navigation is not a bottleneck for Marc, who declares: "I learned to navigate with nothing, at the time there was no GPS but a Gonio and so I acquired the basics of instrument navigation, in autonomy, but I also like to use today's means and technologies. And anyway, the Northwest Passage is accessible via a predefined route, which doesn't leave a huge amount of latitude in terms of overall trajectories."

It's true that in these parts, as in most of the sailing areas frequented by blue water cruising, common sense dictates that we adhere unreservedly to the precepts laid down by the Italian astronomer Cassini (1625-1712), who said: "It's better not to know where you are, and to know that you don't know, than to believe with confidence that you are where you are not". Wisdom that Marc Pédeau would certainly not disavow: "We crossed the Northwest Passage in conditions that enabled us to do some real sailing, at least on the first part of the route, as for example on the west coast of Greenland, where we only used inland passages with rather symbolic but nonetheless effective buoyage. It was necessary to navigate very scrupulously, including on sight, as digital cartography is sometimes inaccurate, even false, to the point where we relied on two separate mapping systems. We navigated outside by sight, with the help of digital tools."

It was necessary to carry out very scrupulous navigation, including on sight, as digital mapping is sometimes inaccurate or even false, to the point where we were relying on two separate mapping systems. We navigated outside by sight, with the help of digital tools."

On this route, we also have to reckon with fairly significant current regimes. In Greenland, from this point of view, the currents were rather favorable, then in Nunavut it was still manageable, and then we encountered current regimes that were always contrary from Cambridge Bay onwards, and therefore for the whole of the end of the course, which is quite long after all, with around 1,900 miles from Cambridge Bay to Nome. On this stretch of the route, we sometimes had to contend with very strong currents, and even more so on the approach to the Bering Strait, where to pass certain capes we had to face head-on currents of 5 knots and more - and in some conditions, which we fortunately didn't encounter, reaching 16 knots."