The Allures 44 Opale has crossed the North-West Passage : 4/5 - The notion of risk in navigation

In August 2019, the Allures 44 Opale crossed the Northwest Passage. The success of this 4500-mile route is the culmination of years of passion for sailing in the Far North for Marc Pédeau and Bénédicte Michel, the discreet authors of this performance. Continuation of articles number 1; number 2 and number 3.

What were the main navigation difficulties encountered?

It soon becomes apparent that navigation is not a bottleneck for Marc, who declares: "I learned to navigate with nothing, at the time there was no GPS but a Gonio and so I acquired the basics of instrument navigation, in autonomy, but I also like to use today's means and technologies. And anyway, the Northwest Passage is accessible via a predefined route, which doesn't leave a huge amount of latitude in terms of overall trajectories."

It's true that in these parts, as in most of the sailing areas frequented by blue water cruising, common sense dictates that we adhere unreservedly to the precepts laid down by the Italian astronomer Cassini (1625-1712), who said: "It's better not to know where you are, and to know that you don't know, than to believe with confidence that you are where you are not". Wisdom that Marc Pédeau would certainly not disavow: "We crossed the Northwest Passage in conditions that enabled us to do some real sailing, at least on the first part of the route, as for example on the west coast of Greenland, where we only used inland passages with rather symbolic but nonetheless effective buoyage. It was necessary to navigate very scrupulously, including on sight, as digital cartography is sometimes inaccurate, even false, to the point where we relied on two separate mapping systems. We navigated outside by sight, with the help of digital tools."

It was necessary to carry out very scrupulous navigation, including on sight, as digital mapping is sometimes inaccurate or even false, to the point where we were relying on two separate mapping systems. We navigated outside by sight, with the help of digital tools."

On this route, we also have to reckon with fairly significant current regimes. In Greenland, from this point of view, the currents were rather favorable, then in Nunavut it was still manageable, and then we encountered current regimes that were always contrary from Cambridge Bay onwards, and therefore for the whole of the end of the course, which is quite long after all, with around 1,900 miles from Cambridge Bay to Nome. On this stretch of the route, we sometimes had to contend with very strong currents, and even more so on the approach to the Bering Strait, where to pass certain capes we had to face head-on currents of 5 knots and more - and in some conditions, which we fortunately didn't encounter, reaching 16 knots."

For the sailor, quantifying the risk is a constant challenge, and you have to take into account a number of factors: weather, currents, sea state, boat and crew, provisioning, energy autonomy, knowledge of the environment, and even reliability of information... To which, in the case of this crossing of the North-West Passage, you have to add the study of ice conditions, which represent a criterion of central importance at these latitudes".

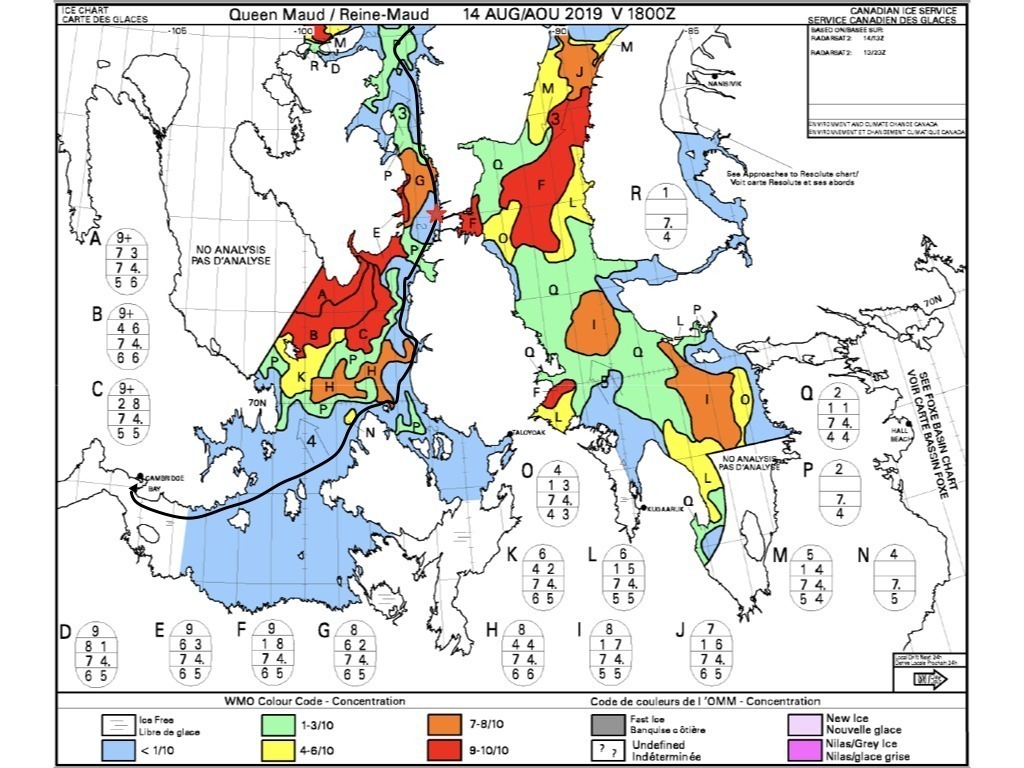

Pleasenote that venturing into the maze of Nunavut islands at nearly 75°N requires some prior knowledge, as the terminology and standards for describing said "ice conditions" are quite complex. These data are standardized by the World Meteorological Organization, and summarized in a very didactic way by the Canadian government's reference site on the Canadian Arctic zone. The site provides a high level of knowledge of Arctic glaciology and how to describe the ice, its formation, age, evolution and characteristics. This is accompanied by monitoring systems marked by the regular issue of highly operational forecast bulletins, which require a good deal of study before they can be understood and correctly interpreted.

How does the presence of ice increase the risks involved?

"The main risk is of course getting stuck in the ice, due in particular to bad information, or misinterpretation of information. In Greenland, we didn't have any particular worries from this point of view because there wasn't much ice. The icebergs were concentrated mainly around Disco Bay, where numerous glaciers pour out blocks of all shapes and an astonishing variety of hues, each more beautiful than the last. In Nunavut, we were able to take advantage of information issued by the Canadian Ice Service and accessible via the Iridium network. These were mainly ice charts giving the concentration and quality of the ice (young ice, old ice, ....); these charts are essential for navigation in this area.

The Canadian Ice Service also issues a light text document giving ice opening forecasts: the document published at the beginning of July gave us opening projections for the entire passage. As it happens, this document gave less optimistic forecasts than the reality actually observed on site. The availability of this data is an obvious advantage for those wishing to make a success of the North-West Passage, with a very interesting level of information, but it in no way guarantees success, and if in any case you're not in the area at a time when it's practicable, you won't be able to get there at the right moment. It has to be said, then, that we were lucky enough to benefit from favourable conditions that summer. In fact, if we look at the state of the pack over the last 20 years, we can say that it was an average year in terms of ice."

The accessibility of this data is an obvious advantage for those wishing to successfully complete the Northwest Passage, with a very interesting level of information.

The summary of the Arctic Waters of North America Seasonal Summary for summer 2019, published after the season by the Canadian Ice Service, says it all: "Due to early ice fracture in the southeastern Beaufort Sea, northern Baffin Bay and northwestern Hudson Bay, ice conditions (sic) were below normal during the first part of the 2019 season. In fact, the rapid decrease in ice extent in the southeastern Beaufort Sea region is attributable to persistent strong southeasterly winds during the latter part of May. As a result, the pack ice shifted to the northwest. Temperatures in the region were also well above normal during this month (May). (...) From late August to early September, most of the Northwest Passage was bergy water or open water".

What about the cold?

"We didn't suffer hugely from the cold on the Northwest Passage section proper. We had been much colder before, in Maine and Nova Scotia, because our Reflex diesel heater wasn't working normally due to a deficient air supply. In the morning it was 2°C and during the day a maximum of 8/10°C inside the boat.

An efficient heating system is essential for anyone embarking on this journey.

When the stove was repaired by an ingenious friend from St-Pierre-et-Miquelon, we were able to put the heating on at anchor. While sailing, the weather was quite mild, say between 5 and 8, or even 12 to 15°C, so the cold wasn't a real problem, even though we were heavily covered. But be warned, an efficient heating system is essential for anyone attempting this route. We were also very interested in the water temperature, as it is a valuable indicator of the proximity of the ice. And of course, when the water temperature around the hull is 1.5°C, it's clear that it's not very warm inside, but it's never been so hard to bear in Greenland and in the passage."

Suiteet fin de cette série : L'Allures 44 Opale a franchi le passage du Nord-Ouest : 5/5 - De l'Arctique à l'Antarctique

latest news

latest experiences

.jpg)

%402x.svg)